‘We are perceivers. We are an awareness; we are not objects; we have no solidity. We are boundless. The world of objects and solidity is a way of making our passage on earth convenient. It is only a description that was created to help us. We, or rather our reason, forget that the description is only a description and thus we entrap the totality of ourselves in a vicious circle from which we rarely emerge in our lifetime.‘

― Don Juan

● Cognitive neuroscientist Donald Hoffman posits that human perception is shaped by evolution not to see objective reality, but to enhance survival by hiding the truth and presenting a user-friendly interface. Using the metaphor of a computer desktop, Hoffman argues that our sensory experiences are akin to icons, representing useful functions rather than the true nature of the underlying reality, suggesting that what we perceive (e.g., a red car) is not an accurate reflection of objective reality.

● According to Hoffman, natural selection favors perceptions that provide fitness payoffs rather than truth. His ‘Fitness Beats Truth’ (FBT) theorem illustrates that organisms perceiving only fitness points outcompete those perceiving objective reality.

● Hoffman challenges the conventional view that consciousness arises from physical processes, proposing instead that consciousness is fundamental and that the physical world emerges from it, thus reversing the traditional hard problem of consciousness.

In this series we explore the scientific theories of three iconoclastic scientists who go against the established views and posit consciousness as the ultimate field of reality. American cognitive psychologist Donald Hoffman (1955) is the most well known of these three consciousness=primary proponents. He did a TED Talk about his views in 2015 – ‘Do we see reality as it is?’ – and was a guest in many popular podcasts, like the popular Lex Fridman and Sam Harris podcasts. His fellow scientists don’t necessarily agree with his theories, but at least respectfully listen to his ideas. He is a great communicator of science who uses smart metaphors to get his ideas across.

The unique way Hoffman goes about it is by tying our perception to evolution. His primary research question originally was: ‘did evolution shape our views to see the truth?’ Not so, concluded Hoffman after years of study. On the contrary, evolution shaped our perspective to hide the truth from us in order for us to survive and thrive.

Whoever once tried psychedelic drugs will have some idea of what Hoffman is on about. While on psychedelics, your sensory impressions intensify and the world gets way more depth, color and radiance about it. The level of detail you perceive also increases dramatically. This may be a mind expanding experience, but due to all the extra input you have to process, survival becomes much, much harder. Try running from a tiger when you have a head full of acid.

Of course you might argue that just because reality gets enhanced by psychedelics doesn’t mean the world is something different than your perception of it. When you take a red car for example, psilocybin may cause it to look extremely red, but it is still a car when you’re not looking that is more or less the same as your perception, right? Not so, according to Hoffman. Whatever reality is, it can not be anything like how we perceive it. The car we observe is merely a symbol for something that moves fast and can get us to the nearest supermarket in no time. Our senses are thus not the windows to objective reality they appear to be.

Picture: FilmDungeon.com

Perception As A Desktop Interface

Our senses are useful, not true, wrote Hoffman in his 2020 book ‘The Case Against Reality’. One of the metaphors he frequently uses is the email icon on the desktop interface. ‘The icon is usually blue, rectangular and in the center of your desktop. Does this mean that the file itself is like that? Of course not. Files have no color. And the shape and position of the icon are not the true shape and position of the icon. In fact, the language of shape, position, and color cannot describe computer files. The purpose of a desktop interface is not to show you the ‘truth’ of the computer – where ‘truth’ in this metaphor refers to circuits, voltages, and layers of software. Rather, the purpose of an interface is to hide the truth and to show simple graphics that help you perform useful tasks such as crafting emails. If you had to toggle voltages to craft an email, your friends would never hear from you.’

Picture: Freevector

The computer desktop is Hoffman’s metaphor for 3D spacetime. The objects you see around you are the icons in your personal 3D desktop. They are completely subjective and thus not present when you are not perceiving them. This goes against most people’s views since most people are ‘metaphysical realists’. They assume that outside of us in the objective physical world are objects and subjects – like green apples and beach-blonde bimbo babes – and our brain constructs a representation of it that closely matches what is really out there.

Hoffman doesn’t deny there is something there in objective reality, but certainly nothing like the things we perceive in space and time. ‘The chance that our eyes see objective reality is effectively zero’(P. 61), according to Hoffman. Still, consensus reality arises because we have all developed our icons in a similar way, because we have similar needs in recognizing threats and fitness payoffs. When we see a snake icon, we run. And when we see a yellow banana, we eat it.

Picture: Free-Consciousness

Evolution shaped our senses to give us the interface we need to be successful in spacetime reality. The interface is tailored to the needs of the species in question. Why does a dog have a different experience than a human when it eats feces? (at least, let’s hope it does!). Because the fitness points for a dog are different than for humans. There is no such thing as objective taste: it is dependent on the fitness an edible object offers to the species observing it.

‘The Case Against Reality’ may not be the most precise title. After all, a ‘reality’ can be defined as any environment governed by consistent rules that all its observers agree upon – something Hoffman does not dispute. What he challenges is the notion of an objectively existing reality – one that remains unchanged, even in the absence of observers. This idea aligns with the core tenets of Free-Consciousness, but Hoffman brings a unique perspective to the discussion: the evolution argument. He contends that perceiving reality as it truly is would have driven our species to extinction. Instead, evolution has shaped our perceptions into simplified icons – functional shortcuts that guide our actions for survival and reproduction rather than offering an accurate depiction of the world.

Picture: Free-Consciousness

Game Theory: Fitness Drives Truth To Extinction

Hoffman’s thoughts were initially shaped by neuroscientist David Marr, who argued that evolution had formed our senses to give us a true representation of the external world. Hoffman became a grad student for Marr who died of leukemia in 1980. By 1986, Hoffman had started doubting his mentor’s claim that we evolved ‘to see a true description of what is out there’. He also doubted that the language of our perceptions – the language of space, time, shapes, colors, textures, smells, tastes, and so on – can frame a true description of what is there. It is simply the wrong language.

Consider two sensory strategies: truth sees the structure of objective reality as best as possible; fitness sees none of objective reality, but is tuned to the relevant fitness payoffs. ‘You may want truth, but you don’t need truth’, writes Hoffman. ‘You need simple icons that show you how to act to stay alive.’ Evolutionary success depends on collecting fitness points. If our senses evolved and were shaped by natural selection, then they inform us about fitness – not about truth or objective reality. This is proven in the Fitness Beats Truth (FBT) theorem, which Hoffman has conjectured and Chetan Prakash proved.

Picture: YouTube (World of Longplays)

Suppose there is an objective reality of some kind. Then the FBT Theorem says that natural selection does not shape us to perceive the structures of that reality. It shapes us to perceive fitness points, and how to get them. Seeing the truth would cost a huge amount of energy, but adds nothing to fitness. This is demonstrated by Hoffman in many simulation games in which certain agents were programmed to see the truth and others to just perceive the fitness points. The outcome was the same every time: truth goes extinct. According to the theorem, the probability is zero that we see reality as it is. It applies not just to taste, color and odor, but also to shape, mass, position and even to space and time themselves.

‘Objects are not pre existing entities that force themselves upon our senses’, writes Hoffman. ‘They are solutions to the problem of reaping more payoffs than the competition, from the multitude of payoffs on offer. I always see a spoon[1] because I need a quick solution. My mind can’t help it. It’s my habit.’(P. 81)

If evolution programmed us to see fitness points, not truth, then the brain with all its neural activity is not true either. It is just a symbol. And if it is just a symbol, how can it be the creator of our conscious experiences?

Picture: Etsy

The Hard Problem Of Consciousness, Flipped Around

According to Hoffman, 99 percent of his colleagues believe that consciousness is the result of complex neural activity in the brain. This is the accepted paradigm in science, just like the assumption that the universe is a physical entity. The problem, which has been identified by philosopher David Chalmers, is that if that is your position you have to explain precisely how physical processes in the brain can create an experience, say the tasting of honey, and why this brain activity does not cause another experience of, for example, hearing a wailing sound. This is the so-called Hard problem of consciousness: how does the feeling of what it is like to be something arise? According to Hoffman, no plausible ideas of how this is possible have ever been proposed.[2]

Our experiences simply don’t appear to be physical at all. ‘What is the mass of dizziness, the velocity of a headache or the position of the wonder why Chris won’t call?’, the professor writes. ‘Dizziness is not the kind of thing that can be weighed on a scale; a wonder has no spatial coordinates; a headache cannot be clocked with a radar gun.’(P. 4)

All explanations produced thus far have failed to explain consciousness because they make the false assumption that objects in spacetime exist when not observed and have causal powers. ‘This assumption works admirably within the interface, but utterly fails to transcend the interface: it cannot explain how conscious experiences might arise from physical systems such as embodied brains, because the underlying assumption is false. Objects have no independent existence when not observed. This statement is informed by our best science: spacetime is not fundamental, so the whole framework of current consciousness research is doomed.’(P. 180)

Video: The Institute of Arts and Ideas

So, Hoffman turned it around. In his theory, called ‘conscious realism’, consciousness is a given. It exists. It is his one free miracle and he will not explain how it arose. His job is, taking this as a starting point, to explain how the physical world arises from it. In Hoffman’s view, spacetime and objects in spacetime are the format of a data compression algorithm that evolution has built into us. Our minds cannot process dozens of dimensions, but we can handle a few; this is our three dimensional window of perception. Hoffman in the Lex Fridman podcast: “How do you start with experiences, like the taste of chocolate, and build up the world from there. How do you get space and time from that? Or what we consider brains? That is my hard problem.”

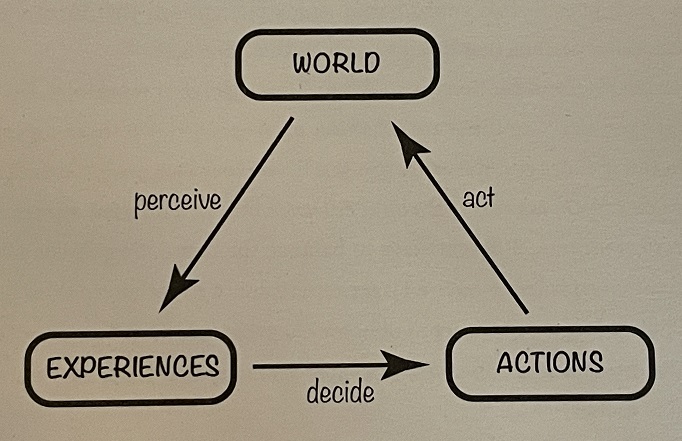

Our interaction with this window of perception is captured by Hoffman in his perceive-decide-act loop:

Picture: The Case Against Reality

We are conscious agents that have a repertoire of experiences and actions that drive our behavior. Based on our current experience, we decide what our next action will be. The action is a bet on a desirable future state of the world. Once the action is taken, the state of the world is updated. Thereby, the experience of the agent is changed. This triggers another decision and the loop goes on and on. According to Hoffman’s theory, natural selection shapes this loop so that experiences guide actions that enhance fitness.

Summarised, perception is the process of decoding information about our fitness and translating that into the most useful interface our minds can create. This interface uses the language of objects with shapes, positions, colors and motions to guide our actions and helps us be successful in the game of evolution. The better our interface, the better we can adapt to our environment and flourish.

‘Our eyes are reporters on the fitness beat’, concludes Hoffman. ‘Always searching for a scoop, looking for intelligence about fitness that is worth decoding. A message, once decoded, typically appears in a standard format. We see the decoded message as an object in space; its shape, category, location and its velocity if moving. We constantly scan for anything animate. We may also scan for high-calorie foods. This repertoire of strategies in our search for fitness payoffs makes the process of searching itself more fit.’(P. 173)

Picture: Free-Consciousness

Summary

‘Spacetime is doomed’, said Nima Arkani-Hamed, particle physicist and winner of the Fundamental Physics Prize 2012. ‘There is no such thing as spacetime fundamentally in the actual underlying description of the laws of physics. That’s very startling, because what physics is supposed to be about is describing things as they happen in space and time. So if there’s no spacetime, it’s not clear what physics is about.’

Hoffman provides an answer to this problem. Spacetime is not an ancient theater erected long before any stirrings of life. It is a data structure that we create now to track and capture fitness payoffs. Physical objects such as coconuts and quasars are not antique stage props in place long before consciousness took the stage. They too are data structures of our making. The structure of a coconut is a code that describes fitness payoffs and suggests actions a conscious agent might take to ingest them. Its distance in space codes the agent’s energy cost to reach it and snatch it! Physics is about figuring out how this interface of our consciousness works.

Perception is the process of decoding information about your fitness and translating that into the symbolic language of your personal reality interface – the language of objects with shapes, colors, positions and motion. This results in guidance for your next – undoubtedly super successful – action.

In the third and final part of this trilogy of essays about paradigm shifters, we discuss the ideas of Thomas Campbell.

1. HOW IT WORKS – ‘A spoon is an icon of an interface, not a truth that persists when no one observes. My spoon is my icon, describing potential payoffs and how to get them. I open my eyes and construct a spoon; that icon now exists, and I can use it to wrangle payoffs. I close my eyes. My spoon, for that moment, ceases to exist because I cease to construct it. Something continues to exist when I look away, but whatever it is, it’s not a spoon, and not any object in spacetime. For spoons, quarks, and stars, conscious realism agrees with Berkeley that Esse is percipi – to be is to be perceived.’(P. 79)

“There is no spoon”

2. There are however many experiments, Hoffman describes, that show the correlation between neural activity and conscious experience. For example, Merel Kindt, a psychotherapist in the Netherlands, cures arachnophobia by asking the arachnophobe first to touch a live tarantula, thus activating the phobia and its NCC (neural correlates of consciousness). She then asks the patient to take a forty-milligram pill of propranolol, a B-adrenergic blocker that disrupts the NCC from being stored back into memory. When the patient returns the next day, the phobia is gone. This can be interpreted as the conscious experience being caused by neural activity, but like any scientist knows, it is easy to mistake correlation with causation. About how the neural activity would do this, creating consciousness, no plausible theories exist, states Hoffman.

Leave a reply to First Seeds (1): What Is The Mental Universe Theory? – Free-Consciousness Cancel reply